The Ancestors Of George & Hazel Mullins

by Philip Mullins

Chapter 9 - William and Solomon Simmons

1824-1860

Summary: William Simmons patented 640 acres

of land in Pike County between 1833 and 1854. His son, Solomon,

patented several hundred acres near that of his father. Many

local men traveled to Washington, Mississippi, during the land

rushes of 1836 and 1854.

The Simmons family was important and influential in their

community. William was a deacon in his church and a member of the state legislature

in 1846. Solomon built his farm into a profitable and self-sufficient enterprise.

He too was elected to public office in Pike County.

The early years of William Simmons

William was the oldest of Ann Simmon's five sons. Upon him fell the responsibility

of running the family farm after the death of his father in 1814. He assumed

the leadership of his brothers and of his mother's servants in working the farm.

He and his brother, John, who was only a year younger, were particularly close.

They worked together, courted together, married sisters and attended to the

business of their church together. In the early years of their marriages they

probably farmed together as well.

For some time prior to 1824 William

had been courting Nancy Hope. She was the eldest daughter of James Hope, a local

justice of the peace.

William and John courted the Hope sisters, Nancy and Mary, together and married

them at about the same time. Nancy Hope was 17 when she and William married.

She was, like William, the third child of a large family and the oldest of her

sex. Her sister Mary was two years younger. It is likely that these two older

sisters, married to two older brothers, each pair very close in age and good

friends throughout their lives, formed a single family in their younger years

and remained very close throughout their lives.

William and Nancy built a house east of Mt. Zion Church about a half mile

from that of Ann Simmons

and about two miles from that of Nancy's parents. Over a period of years the

couple entered a good deal of public land. Early township plats in the Pike

County Courthouse show that William patented 160 acres in 1835 and another 160

acres in 1836. Eighteen years later in 1854 he patented an additional 320 acres.

Altogether William entered 640 acres in a block about a quarter of a mile east

of Mt. Zion Church. In 1860 Census he estimated that his real estate holdings

were worth $2500. He could be described as comfortable well off.

Before the 1860s it was necessary to travel to the US Land

Office at Washington, Mississippi, to register a land claim and to pay the registration

fee. William made the trip to patent land three times, twice in the 1830s and

again in 1854. In March 1803 the US Congress enacted a law that provided for

a survey of the land ceded by the State of Georgia. The whole area was to be

divided into sections of one square mile each. Each section contained 640 acres

and was subdivided into quarter sections of 160 acres each. Quarter sections

were further divided into 40-acre lots. This same law set a registration fee

of 50 cents an acre and mandated that a land office be opened in Washington,

Mississippi.

Between 1810 and 1833 less than 10% of the land in Pike County was registered

or patented by settlers. In the winter of 1817 Henry Bond registered 80 acres

and then a year later he and two other men registered a total of 240 more acres.

Between then and 1832 only one settler bothered to make the trip to Washington

and pay the registration fee. One 40-acre lot was patented in 1832 and another

in 1833. In September 1835 William Simmons patented 160 acres, paying a fee

of $200. By 1830 the registration fee had increased to $1.25 per acre.

In the winter of 1835 something happened to convince the settlers that they

needed titles to their farms. Between March and December 1836 about thirty men

patented their land. Many of these farmers had been working their farms for

20 years by then without ever feeling the need to have legal title to it. Now

they traveled to Washington alone or in groups as large as six. Robert Strickland,

a brother of Henry Strickland

, made the trip three times and spent $200 to register 160 acres, most of it

in one block. William Simmons had registered 160 acres the year before but he

returned to the registry office again in November 1836, paid another $200 and

registered another 160 acres adjacent to his farm near Mt. Zion Church. His

mother, Nancy Simmons,

finally patented her 40 acres in September 1836. George Simmons patented 160

acres and John Simmons patented 40 acres.

By the end of 1836 about 38% of the county had been patented despite the extremely

high fees charged by the Land Office..

Between 1836 and 1851 no land at all was patented in Pike County. In 1851

when he was 25 years old, Solomon Simmons

went to Washington and registered 80 acres. Solomon was the first of a new generation

of farmers to seek title to their land. Over the next ten years 60% of the land

of Pike County would be patented in what could only be described as a rush for

land created by the "bit law."

The Land Rush of 1854

In the early 1850s the US Department of the Interior authorized the registration

of up to 160 acres of land per person for a fee of 12 and one-half cents per

acre. The previous fee had been $1.25 per acre. This regulation was called the

bit law because 12 and one-half cents was one bit or one-eighth of a Spanish

silver coin that had the value of one dollar. This coin was minted in Mexico

City. The Americans called it a doubloon. They often cut the coin into eight

bits or pieces and used them as fractional currency. Two of the bits were worth

one-quarter dollar, four were worth one-half dollar and six were worth 75 cents.

Until the 1870s the US suffered a chronic and severe shortage of coins and,

since the doubloon was accepted as legal tender in the US, it and other Mexican

coins were the common currency in Mississippi.

After the bit law became effective speculators and land grabbers began to

patent all available public land even if it was already occupied. Most settlers

had not bothered to get title to their land and it was possible for the land

sharks to go to the land office in Washington, enter the land in their own names

and then attempt to force the occupants to buy the land or get out. Congress

did not pass a homestead law until 1862 so there was no occupancy requirement

to get title to the land. Since the going price for undeveloped land was 50

cents per acre, the scheme could be quite profitable if it worked.

It was actually tried on more than one occasion in northern Pike County and

as a result there was a great rush to the land office of farmers looking to

protect their land from the sharks. The rush to the land office in 1853 and

1854 was so great that all lodging facilities in the town of Washington was

taken and men were forced to camp in the woods. There was only one registrar

so the men sometimes had to wait for days for their turn at the registry book.

During the fall of 1854 a great many men from Pike County made the trip to

the land office. The three Simmons brothers and William's son, Solomon, were

joined by their McElvin, Strickland, Hope and Sandifer kin in the rush to the

land office. Many of these men had already patented their farms in the land

rush of 1836. Now they were snapping up any available acreage surrounding their

farms. George Simmons

patented 320 acres on November 17, 1854 and 40 more the next fall. On November

21 William Simmons

patented 240 acres and a week earlier his son Solomon patented 240 acres. Henry

Strickland

, now over 50 years old, patented 120 acres. By the end of November 1857 the

land rush in Pike County had about played out and over 90% of the acreage of

Pike County had passed into private hands. Much of the land patented during

the 1850s was not cleared for farms. It was held in reserve for the next generation

and, in some cases, for the one following that. As late as 1915 some farmers

in the area were offering a gift of 40 acres of land to their children upon

their marriage. In the meantime the unimproved land served as wood lots and

as a source of cash in the event of some emergency.

Travel by ox-cart

Prior to 1850 there were fewer than half a dozen horse-drawn buggies in Pike

County. The farmers used ox wagons

when hauling, and, if available, horses or mules for light travel. As a rule

two or three men driving two or three teams of oxen made long trips together

for safety and companionship. Prior to the 1850s the nearest town was Holmesville

in northern Pike County. It was the county seat and the commercial center of

the surrounding area. Holmesville is on the banks of the Bogue Chitto River

and may have been where cotton was taken for sale. The village was only five

or six miles from Emerald

and the trip would have taken two hours to go and two more to return. However

much of the region's cotton was carried to the Natchez market by way of Liberty.

Since Natchez was 60 miles northwest of Liberty and Liberty was 35 miles west

of Emerald, the trip would have taken no less that three days of steady travel

to go and another two or three to return. It seems unlikely that farmers in

Pike County would have risked a trip of that duration loaded with a ton of cotton

but it possible.

In his 1983 book titled "Knippers", Prentiss Knippers reprinted

an excerpt from a book by C.C. Knippers. The excerpt describes travel by ox

cart. The following quotation is taken from that book. "The nearest railroad

town...where we bought our supplies was about 30 miles away so we made the journey

only about twice a year. We went in an old ox wagon which was built in the blacksmith

shop. When my father went to town the neighbors would go with him. They would

take about three ox wagons. It took three days and part of the nights to make

the trip. They would camp one night on the way and then drive into town the

next morning.

"I remember one day when father said

that I could go with him to town. I can see myself now as my

mother got me up early and dressed me for that exciting trip.

Old "Spot" and old "Rowdy" were yoked up

and hitched to the wagon and we started out before daylight on

our "long" journey. The roads were muddy and sometimes

our wagon would bog down. Some of the neighbors who were with

us would hook their oxen on and pull us out. We finally got

to the old camping place for they had a certain place where they

always camped. We started on our way early the next morning.

"When we arrived we unyoked the oxen

and fed them. We went to the grocery store, bought some salmon,

sardines, cheese and crackers and sat down on the ground and spread

our supper. We looked the little town over and then my father

said, 'At 8:30 it will be time for the train to come through.'

I had never seen a train,. My father, uncle Bill Stewart

and Walt Sterling...took me to the depot to see the train. The

big headlight of the train soon appeared and the closer it got

the larger it looked and the more frightened I became. As it

rolled up to the depot my father said, 'Son, it won't hurt.'

But he did not convince me and as it got within about 50 steps

of us my father got me by one hand and Walt by the other to keep

me from running away. It took me about two hours to get over

the excitement.

"We then went back to the camp yard,

spread some quilts on the ground and slept until about daylight.

When the teams were fed we loaded our groceries and dry goods

and started home."

This account describes conditions in western Louisiana

in 1900. In Pike County, Mississippi, oxen were routinely used to haul heavy

loads until about 1905. After about 1905 farmers all over the South sold their

oxen

and home-made wagons and purchased a pair of horses and a

factory-made wagon. Prior to 1825 and for many years afterward, farmers did

travel between Natchez and Pike County by ox-wagon. The time involved and the

extremely high cost of registering land prevented many farmers from getting

legal title to their farms until the 1850s.

The later years of William Simmons

Prior to 1838 William

and his brothers and their families attended the Silver Creek Baptist Church,

traveling the seven or eight miles back and forth together. In 1833 letters

of dismissal were granted to all of them, presumably in an unsuccessful attempt

to organize a church closer to home. In 1838 letters of dismissal were again

granted and Mt. Zion Church was organized. When Mt. Zion

Church was organized William and one of his brothers-in-law were ordained to

serve as deacons. John Simmons was elected church clerk.

William's wife, Nancy, was elected a deaconess at the same time. Nancy must

have been held in high regard by her neighbors because, while women deacons

are not unknown in Baptist churches, they are very rare. Nancy continued to

serve as a deaconess until her husband died in 1867.

Nancy's sister, Mary, joined the new church two days after its organization

during the protracted revival meeting that customarily followed the founding

of a new church.

William was an important man in the Gladhurst-Emerald community. He was captain

of the militia company to which he belonged and in 1846 he was elected to the

Mississippi State Legislature from Pike County. He was a successful farmer and

the father of eight children. He survived the Civil War and died in 1867 at

the age of 65. His wife Nancy continued to live in their home until she sold

the farm to her youngest son 14 years later. She went to live in the home of

her daughter just east of Magnolia where she died in 1888.

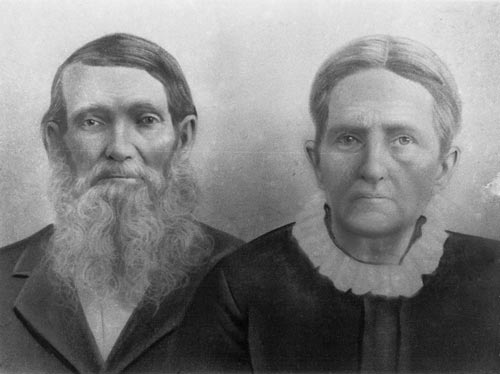

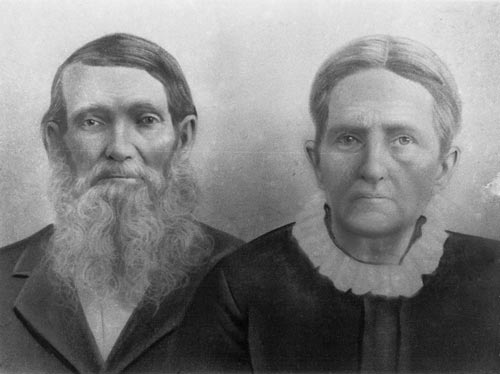

Solomon and Sophronia Simmons

Solomon and Sophronia Simmons (1900)

09-1 |

Solomon Simmons

was the first child of William and Nancy Simmons and the sixth of the 76 grandchildren

of Nancy Ann Simmons. He was born on August 4, 1825 when his mother was 18 and

his father 24. He spent his early years either at his grandmother's house or

at the new log home his father was building just east of where Mt. Zion Church

was later built. His father did not patent his first 40 acres of land until

10 years after Solomon was born, so it is possible that Solomon spent his first

10 years at his grandmother Simmon's home. Solomon knew his grandmother well.

He called her Nancy, a nickname for Ann.

He took an interest in the history of his family and passed along to his grandson

what little we know about his grandparents.

By the time William had patented the land he had chosen for his own farm,

he and Nancy had four children: Solomon and three baby girls. In all William

and Nancy had eight children born between 1825 and 1847. There were six girls

and two boys. Until Solomon was 15 he was the only son. While Solomon was young

some accident or illness caused one foot to be smaller than the other and he

was lame throughout his life. This handicap was not a serious impediment in

his long and active life as a farmer. He was active in community affairs and

had a hand in starting the first school in the area. He is cited as having been

particularly helpful to his sister-in-law Mary Ann Sibley following the death

of her husband. He served briefly as a soldier during the War between the States

and in late life was an elected member of the Pike County Board of Supervisors.

He raised a large family and left a debt-free estate of several hundred acres

and a virtually self-sufficient farm. The humble log dwelling he built in the

1850s was still occupied by one of his descendants in 1987.

In 1849 Solomon married Sophronia Varnado. Sophronia

(pronounced so-fro-knee with the accent on the middle syllable) was the oldest

daughter of Samuel Varnado Jr. She was a grand-daughter of Samuel Varnado Senior

who had come from South Carolina in 1811. Sophronia's mother, Keziah Newsom

, had come to Mississippi from South Carolina or Georgia as an unmarried woman.

In 1812 she married Samuel Varnado Jr.

when she was 20 and he 19 years old. Keziah and Samuel farmed in Pike County

and raised 10 children. One of Sophronia's brothers became a medical doctor.

Sophronia and Solomon Simmons raised nine children, nearly all of whom lived

all of their lives within a mile or two of the Solomon Simmon's farm, a short

distance southeast of Emerald and about a mile from Nancy Simmon's house.

Solomon patented most of his land on November 14, 1854 when he, his father

and his uncles made the trip to the land office in Washington during the land

rush caused by the bit law.

In the1860 Census he estimated that his real estate holdings were worth $1800.

During his lifetime, he built his farm into a model operation which became a

center of community life. His youngest son, George Johnson,

inherited the farm. According to W.W.Simmons, "By thoughtful management

and unselfish generosity, Solomon created a farm whose prosperity and diversity

made it an influential and enduring institution in Pike County". Sophronia

died in 1904 and Solomon followed four years later. W.W. Simmons says that "When

he died at the age of 82, all of his nine children were still living, there

were no debts and his estate was not administered by court but his children

made an equal division of personal effects and his lands were conveyed by joint

deed of the heirs to the youngest son, George J. Simmons."

Solomon Simmons family group photograph (1900)

09-4 |

Back to Table of Contents

| Chapter 10

Copyright © 1994-2005

by Philip

Mullins. Permission is granted to reproduce and transmit contents for not-for-profit

purposes.